One argument that has never flown with me is that foie gras should be easy to ban because it’s an unnecessary, decadent luxury. I appreciate the slippery-slope arguments about such distinctions, but I object on more basic grounds: Food isn’t just fuel. It’s a source of pleasure, and if some people love foie gras the way others love chicken nuggets, who are we to say one dish is frivolous while the other is acceptable?

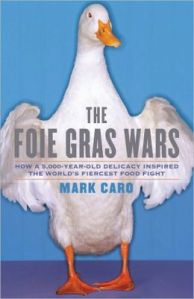

I just finished this book, subtitled “How a 5,000-year-old Delicacy Inspired the World’s Fiercest Food Fight”, and let me tell you: I am seriously jonesing for some foie gras.

I just finished this book, subtitled “How a 5,000-year-old Delicacy Inspired the World’s Fiercest Food Fight”, and let me tell you: I am seriously jonesing for some foie gras.

Well really. You give a foodie a book that goes on for over 300 pages about the author’s exploits from Chicago to New York to belly-(or should that be liver?)-of-the-beast France, tasting the pinnacle of what haute cuisine can offer in terms of flavor, and you don’t expect me to be wiping a little drool from my chin by the end?

My move to California – where a ban on the production and sale of foie went into effect just last year – was ill-timed.

But about the book. I enjoyed it a lot and learned a great deal. I now know the entire process of creating a foie gras liver, including how gavage (force-feeding) is accomplished. I know a bit about its history, dating back to the Egyptians, and that it is mentioned in a number of Greek and Roman writings (including by such favorites as Homer, Pliny the Elder, and the poet Horace – that’s just a little historical geekery for that segment of my audience). And I even know how to make the Medieval dish “A Goose Roasted Alive” (although I don’t recommend trying it at home, and to his credit, Cato* only references it – I had to google the actual recipe).

But the most interesting thing to me personally was to discover that this whole thing is not so Cali-centric as I once thought. Caro places the “shot heard round the culinary world” squarely in his hometown of Chicago, the first American city which banned the dish – and subsequently (spoiler alert!) repealed the ban, called by Mayor Daley the “silliest” piece of legislation ever passed by his fair city.

Caro spends a great deal of time covering the fight over foie in Philly (say that three times fast), a section of the book that gets downright bitchy in its gossipy renditions of the feuds and fawnings of chefs, animal rights activists, celebrities, and politicians. Honestly I never would have pegged Philadelphia as the city where much of this worldwide fight would go down, but Caro certainly makes the players memorable and reports the saga in such a way as to make into a page-turner what is basically a schoolyard fight between bullies and victims (each side – chefs and activists – seeing themselves as the latter, of course).

Caro finally finishes up his tour-de-foie in France, the home of the delicacy, where he experiences revelations in both taste and knowledge. The final take on French production is that it is much like American farming: there are good ways to go about it that honor traditions and create excellent results without doing too much harm in the process, and then there are industrial ways to feed the masses that result in inferior product and unnecessary suffering. There is a final exploration of some recent attempts to create a more humane foie gras, which leaves us on a note of hope.

The book stridently attempts balance and often succeeds. Caro certainly seems to second-guess everyone’s motives, push their reasoning, and adds his own commentary to question seemingly-closing arguments. However, I was left with a bad taste in my mouth for the tactics and motives of the animal rights movement. For them to focus with such intensity on this issue, which affects relatively miniscule numbers of the animals in farm production and the eaters who enjoy them, leaves one with the cynical notion that this fight was waged solely because it was an easy win. Some of them freely admit this. They believe it builds momentum towards more important legislation. But another way to look at is: they picked on an easy target (rich people food) just to feel better about their mostly-failed attempts at getting this country’s food system changed.

And the saddest thing about the foie gras wars is this: the vast majority of people who voted into law bans on the sale or production of this ingredient (including much of California’s voting populace) has never tasted it, probably wouldn’t care to try it, and knows next to nothing about its actual production. Propaganda flies from both sides, but from Caro’s perspective – and he is truly trying to be an investigative journalist here – there is very little about the American way of raising ducks for foie (geese are not used in the States) that is tortuous or even very inhumane. It pales in comparison to the treatment of other poultry (like, say, the 9 BILLION chickens slaughtered every year), not to mention mammals such as sows (kept in gestation crates) or veal calves (also crated). Caro visits the farms, he watches every step of the process from the lengthy time the ducks spend living a regular life outdoors (the ducks spend 12 weeks in relatively normalcy as opposed to a broiler which would never see the light of day and only lives 32 total days anyway), to the force feedings (which turn out to be far less dramatic than he expected), to the slaughter.

Side note: there is a lot of talk about how force feeding is such a travesty because it is dominant and disrespectful of the animal (nevermind that a duck or goose will naturally grow a fat liver – though not to foie gras weight – due to migratory needs). But I don’t really see the difference between feeding an animal corn through a tube inserted in the throat (wide enough to swallow whole fish) vs. genetically engineering an animal so that it grows to a size absolutely never intended by nature in an equally-obscene span of time. I guess the difference is that in the latter example, the animal is force-feeding itself…but still. We engineered that. And we provide the necessary side products (hormones, antibiotics, feedlots) that enable the unnatural behavior.

All that to say that I, like – I think – Caro, don’t really get, when all is said and done, what all the fuss over foie gras was about. It was a distraction, a side issue, and a waste of resources – energy, time, and money.

Here is what it accomplished:

- Animals rights activists can claim a small victory. They may have momentum towards bigger things, but I doubt it, because…

- Regular ol’ meat-eating folks – your friends buying Tyson chicken at the supermarket and McDonald’s hamburgers – can feel like they did real good by those poor tortured animals. They can go on buying their battery cage-produced eggs with a clear conscience because hey, when the issue of animal torture was put to a vote, they did the right thing and said “no” to duck torture. Which, I repeat, produced a product none of them were going to eat anyway.

Yeah. Big win.

Oh and the other thing it accomplished: California’s only producer, Sonoma Foie Gras – one of the two sizeable producers in the entire United States (the other is Hudson Valley Foie Gras in New York) – was put out of business. He basically ran a family farm, and was an immigrant from El Salvador. Now I’m not going to argue that his business was worth suffering on the part of others, obviously (old slavery argument). But what I will point out is that people are still eating foie gras in every other state. And where are they getting it? If not from Hudson Valley, then from Canada and France, where the standards for animal welfare are far lower than in the US.

In other words, all this ban did was transfer the business out of our country, and hand it to people who treat the animals far, far worse. Bravo!

This was a really fascinating book. It was like foodie pulp fiction, with plenty of gore and sass, drama and betrayal. And oh yeah, some very titillating in-depth descriptions of foie dishes.

Which, thanks to the events chronicled, I shall not be consuming anytime soon.

*Editorial note: That was an honest brain fart changing “Caro” to “Cato”…but I loved how it shows my knowledge of historical writers, so it stayed in.